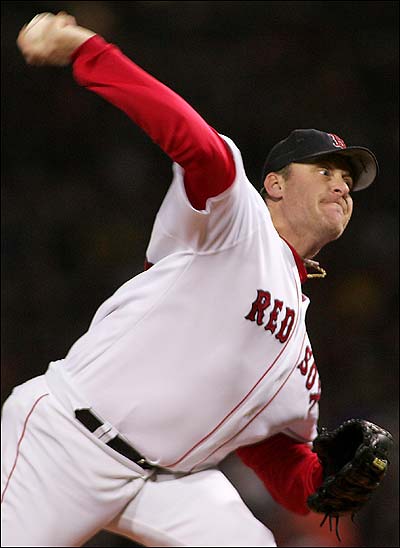

Photo credit: AP via SportsIllustrated.com

The Mitchell Report, a 21-month study of "the steroid age" in baseball, was released yesterday. My first reaction, as it was with the Michael Vick dogfighting case this past summer, is that we have a standard of innocent until proven guilty in this country. In addition, after looking over several pages of the actual report and various excerpts available online at ESPN.com and other media outlets, the bulk of the evidence seems to come from shady clubhouse attendants and MLB and the federal agencies that were already investigating will have to verify that the evidence is sound.

While some names that were mentioned in the report weren't a surprise (Barry Bonds, Gary Sheffield, Jason Giambi - all previously involved with the BALCO investigation), others were very surprising, particularly Andy Pettitte, a starting pitcher for the New York Yankees, and relief pitcher Mike Stanton, known for his Yankees career. These two guys appeared to be great players (Andy is a great competitor and has one of the coolest pickoff moves and Stanton was practically a machine when he pitched.) Both weren't players of the Randy Johnson 20-strikeouts-a-game level, but were known for the way they played the game and being great teammates. Andy was also known as a family man, to the point where he played for his hometown Houston Astros for a few years saying it was for his family.

So what does a fan do now? Do you trust a player that denied steroid use, but was then implicated in the Mitchell Report? Do we punish players retroactively? Personally, as much as I would like to see these players banned from the game and their records/titles stripped (given that the evidence is true and verified), I question what effect that would have. Although they cheated, there wasn't official drug testing until 2002, the year after Barry Bonds hit 73 homers. That is not to say that the players don't deserve blame, but rather guidelines and rules simply weren't in place because the steroid problem wasn't being addressed by MLB, the Players' Association, or the players themselves.

So who deserves blame then? First, the players. The players were the ones willingly taking substances that could cause bodily harm and betraying the fans' trust. No one was forcing them to take the 'roids, but they put themselves at unnecessary risk all for the sake of getting a competitive edge. Second, the Players' Association and MLB. The following is straight from pages SR-11 and SR-12 of the Mitchell Report:

For many years before 2002, the Players Association opposed any drug program that included mandatory random testing, despite several proposals for such a program from different Commissioners. The early disagreements on this issue centered around testing for cocaine and other “recreational” drugs, not steroids, but the effect of the Players Association’s

opposition was to delay the adoption of mandatory random drug testing in Major League Baseball for nearly 20 years.

However, opposition by the Players Association was not the only reason that mandatory random drug testing was not adopted. In 1994, Commissioner Selig and the club owners proposed a drug program that would have included some forms of testing and would have listed steroids among baseball’s prohibited substances. Robert D. Manfred, Jr., who is now executive vice president for labor relations in the Commissioner’s Office, recalled that anabolic steroids were included in the 1994 proposal to be proactive, and the decision to include steroids in the proposal was not based on any particular concern about the use of those substances in baseball at that time. He acknowledged that at the time the drug program was not as high a priority as economic issues.

The Players Association did not agree to the proposal. Officials of the Players Association said that the clubs did not appear to regard the 1994 proposal as a high priority and did not pursue its adoption vigorously. Indeed, Players Association executive director Donald M. Fehr recalled that the proposal never even reached the main bargaining table during

negotiations.

Later that year, a work stoppage ended the season and resulted in the cancellation of the World Series. Play resumed in 1995 without a collective bargaining agreement, and the owners made no attempt to renew the drug program proposal when collective bargaining resumed. That bargaining resulted in an agreement that remained in effect until 2002, so the next

proposal for a mandatory random drug testing program was made in those negotiations with the Players Association in early 2002.

In 2001, the Commissioner had unilaterally implemented drug testing throughout baseball’s affiliated minor leagues. He used that program as the basis for his 2002 proposal to the Players Association for a major league program.

The Players Association did not want much of a drug testing program and to association head Don Fehr's credit, said yesterday, "Perhaps we and the owners could have taken these steps sooner, and for my part in hindsight, that seems obvious." Though the statement comes years late, I can at least appreciate the fact that he said it as opposed to Commissioner Bud Selig's lack of saying MLB itself shared blame. I'll leave you with a great excerpt from Curt Schilling's blog, 38pitches.com:

"There will be no shortage of media opinions, castigating, berating and blaming all the names involved. Just remember that this will be coming from the very same people who, like many, turned a blind eye to what many of us believed when we were smack dab in the middle of all the things the Mitchell Report will say.

I certainly am not blameless. I had opinions like many other people, but I also had a closer view of what was happening. I can say with a very clear conscience, to this day I still have never seen anyone inject or ingest HGH, or steroids. Do I think I know former teammates that may have been? Sure I do. Can I tell you with no uncertainty who that was? No.

And at the end of the day, from everything I hear, that’s what will be contained in the body of this report. Much speculation, conversation, and hearsay, as to what people saw and thought."